"Teen love may feel new, but Romeo and Juliet remind us it’s been the same for centuries—passionate, heartbreaking, and unforgettable."

If you’re the parent of a teenager, you’ve likely witnessed the intensity of young love firsthand. Whether it’s a first crush or a budding relationship, it can be both exciting and overwhelming to watch. While teen romance might seem like a modern experience, Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet reminds us that the highs and lows of young love—passion, heartbreak, and everything in between—have remained unchanged for centuries. Today’s teens still relate to the themes of love, loss, and the emotional whirlwind that comes with it, just as Romeo and Juliet did long ago.

Impulsiveness in Romance

Romeo meets Juliet at a grand ball, and the moment their eyes meet, nothing else seems to matter. Within minutes, they’re swept up in a whirlwind of emotions, declaring their love, and just a few days later, they’re secretly married. It’s passionate, dramatic, and entirely impulsive. Shakespeare gives us one of the most iconic love stories of all time, but let’s be honest—could something like this really happen in real life?

While most teens may not be running off to secretly marry someone they just met, they often experience love with the same intensity and urgency. Impulsiveness is a natural part of growing up, and while it can lead to exciting experiences, it can also bring challenges. That’s why it’s important for parents to recognise these strong emotions and help guide teens to slow down and make thoughtful decisions.

In today’s world, impulsive young love plays out in different ways. A teen might meet someone online, feel an instant connection, and want to meet in person without fully considering the risks. Or they might get caught up in the thrill of a relationship and make big commitments—like making drastic life choices based on emotions in the moment. Social media also intensifies this, with public declarations of love, dramatic breakups, and instant rebounds playing out for everyone to see.

When emotions take the lead without pausing to think things through, things can go awry. Rushing into a relationship, making promises too quickly, or acting without considering the consequences are common pitfalls. It’s not that teens shouldn’t experience love fully, but they often need gentle reminders to take a step back and reflect before making big choices. Love can be exhilarating, but helping teens balance passion with reason can prevent regrets down the line.

Parental Influence

Juliet’s parents, especially her father, Lord Capulet, seem more focused on controlling her future rather than supporting her personal passions or interests. Instead of considering what she truly wants, they make decisions for her, pushing her toward marriage with Paris without regard for her feelings. This lack of understanding only drives Juliet further away, leading to desperate choices.

As parents, it’s crucial to build a strong, open relationship with your teen. When you’re connected, they’re more likely to turn to you for guidance. Without that connection, they may make decisions without considering your input. Teens naturally crave independence, but they also need to feel supported and understood. If they sense that their thoughts and emotions don’t matter, they may rebel or seek validation elsewhere—sometimes in ways that aren’t safe or healthy. Check out: Should Parents Be Concerned About Teen Dating?

A teen who feels unheard at home might keep secrets about their relationships, avoid sharing their struggles, or even make impulsive decisions just to assert their independence. But when parents foster open communication, teens are more likely to seek advice and make thoughtful choices. Instead of just giving advice, truly listening to them can help prevent misunderstandings and offer the support they need to handle tough emotions.

One of the biggest lessons Romeo and Juliet teaches us is that rigid control and lack of communication can push teens toward risky decisions. Allowing them to express themselves and showing that you respect their feelings creates a foundation of trust, empowering them to make better choices. After all, every teen wants to be heard—sometimes, they just need a little space and encouragement to open up.

Heartbreak and Infatuation

At the start of Romeo and Juliet, Romeo is completely heartbroken—not over Juliet, but over another girl, Rosaline. He believes she’s the love of his life and that he’ll never recover from his sorrow. But the moment he meets Juliet, all thoughts of Rosaline vanish. Suddenly, he’s in love again, swept up by the excitement of new emotions. His quick shift from despair to devotion shows just how intense—and fleeting—teenage love can be.

This highlights how young love, while powerful and all-consuming in the moment, often lacks the stability and depth of more mature relationships. Teens experience emotions in extremes, swinging between heartbreak and euphoria in a way that feels overwhelming and entirely real to them. While adults may recognize these feelings as temporary, it’s important to acknowledge that, to a teen, they are deeply significant.

Heartbreak can be especially tough at this stage. A teen experiencing their first breakup may feel like their world is crumbling, much like Romeo does when Rosaline rejects him. Parents can help by validating their emotions. Simply reminding them that heartbreak is painful but temporary can go a long way in helping them process their feelings in a healthy way.

At the same time, it’s important to help teens recognize the difference between short-lived infatuation and deeper, lasting love. They may fall hard and fast, just like Romeo and Juliet, but love isn’t just about intensity—it’s about trust, understanding, and patience.

What Was Shakespeare Trying to Say?

Was Shakespeare celebrating young love, or was he warning us about its dangers? The answer is probably both. Romeo and Juliet’s passion is undeniable, and their devotion to each other is deeply moving. Shakespeare captures the magic of young romance—the excitement, the urgency, and the belief that nothing else in the world matters.

At the same time, he doesn’t ignore the risks. In just a few days, their whirlwind romance leads to secrecy, conflict, and ultimately, tragedy. Their love burns bright, but without patience, guidance, or the space to grow, it becomes destructive. Shakespeare reminds us that while young love is real and powerful, it can also be impulsive and short-sighted, leading to choices made in the heat of the moment rather than with long-term understanding.

This is an important takeaway for parents. Teens experience love with intensity and urgency, but they also need time and perspective to make thoughtful choices. Rather than dismissing their emotions as “just a phase,” offering guidance and support can help them navigate relationships in a healthy and balanced way. Open conversations about love, respect, and emotional maturity can make a huge difference in how teens approach romance.

Ultimately, Romeo and Juliet isn’t just a tragic love story—it’s a lesson in the power and pitfalls of young emotions. Shakespeare doesn’t tell us to fear teenage love, but he does show us why it needs wisdom and patience to truly flourish.

Dig Deeper into Romeo and Juliet

Want to help your teen truly connect with Romeo and Juliet and master English Literature? Our Romeo & Juliet Study Guide: Passage-Based Exam Practice Papers is designed to make Shakespeare’s timeless tragedy more accessible and meaningful. Instead of just memorizing quotes, this workbook encourages deeper thinking, helping teens uncover the emotions, conflicts, and literary brilliance behind the play.

Each practice paper is carefully crafted to guide students through Shakespeare’s language, literary devices, and dramatic techniques. By working through key passages, your teen will sharpen their analytical skills, build confidence, and develop a stronger appreciation for the play’s themes and characters. Plus, with detailed explanations and answers, they’ll gain valuable insights that make studying easier and more effective.

If your teen is preparing for exams or looking to deepen their knowledge of classic literature, this guide will help them develop the skills needed to excel in English Literature.

Order now on Amazon to help them unlock a deeper understanding of one of the greatest love stories ever written. You can also check out our Free Resources for additional study materials on Romeo and Juliet!

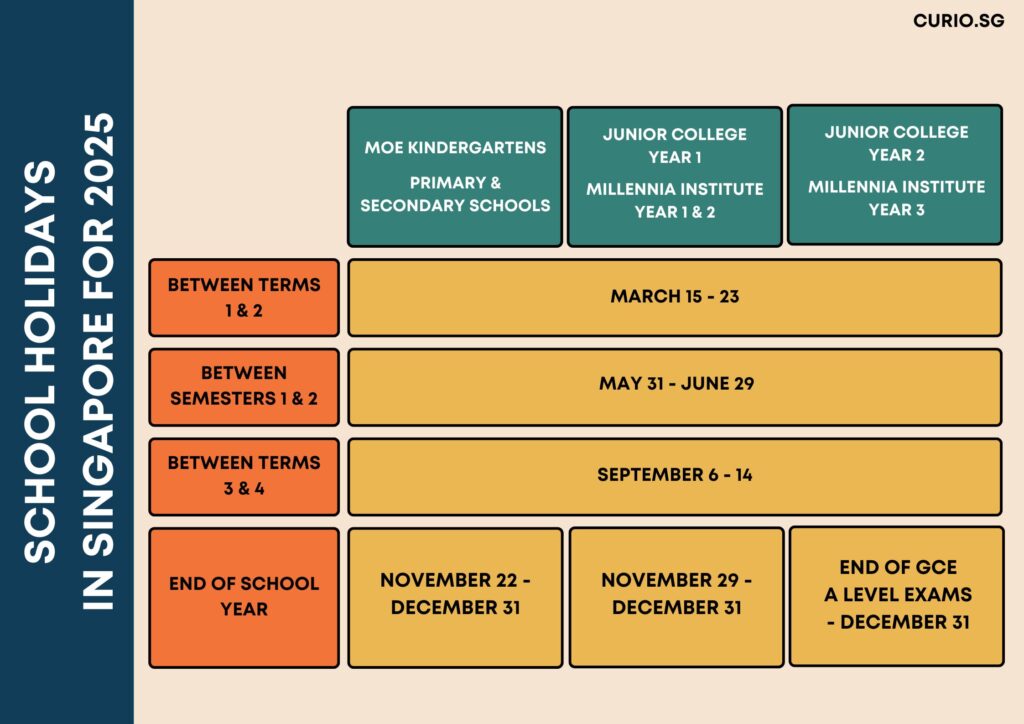

For even more guidance, Curio offers online tuition in English Language, English Literature and General Paper. We cover O-Level, A-Level, and the upcoming Singapore-Cambridge Secondary Education Certificate (SEC) in 2027, as well as English, Literature or Language Arts subjects in the Integrated Programme (IP).

Sign up with Curio today and help your teen gain the skills they need to master Shakespeare—and beyond!